Hassan Vally, La Trobe University

Yesterday’s announcement the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine would now only be recommended for the over 60s has highlighted the many ways we think about risk.

The decision reflects a greater understanding of the real, but extremely low, risk of the clotting disorder called thrombosis with thrombocytopenia (TTS) for people aged 50-59, who are now recommended to have the Pfizer vaccine.

But errors in the way we perceive these extremely small risks, called cognitive biases, reflect the fact that when our brains evolved we did not have to grapple with risks this small. So we struggle to make sense of them and perceive these events as being much more likely than they actually are.

This can lead us to make decisions, such as not having a vaccine that could potentially save our life. And the misperception of the likelihood of TTS is one of the main reasons many are hesitant about receiving the AstraZeneca vaccine.

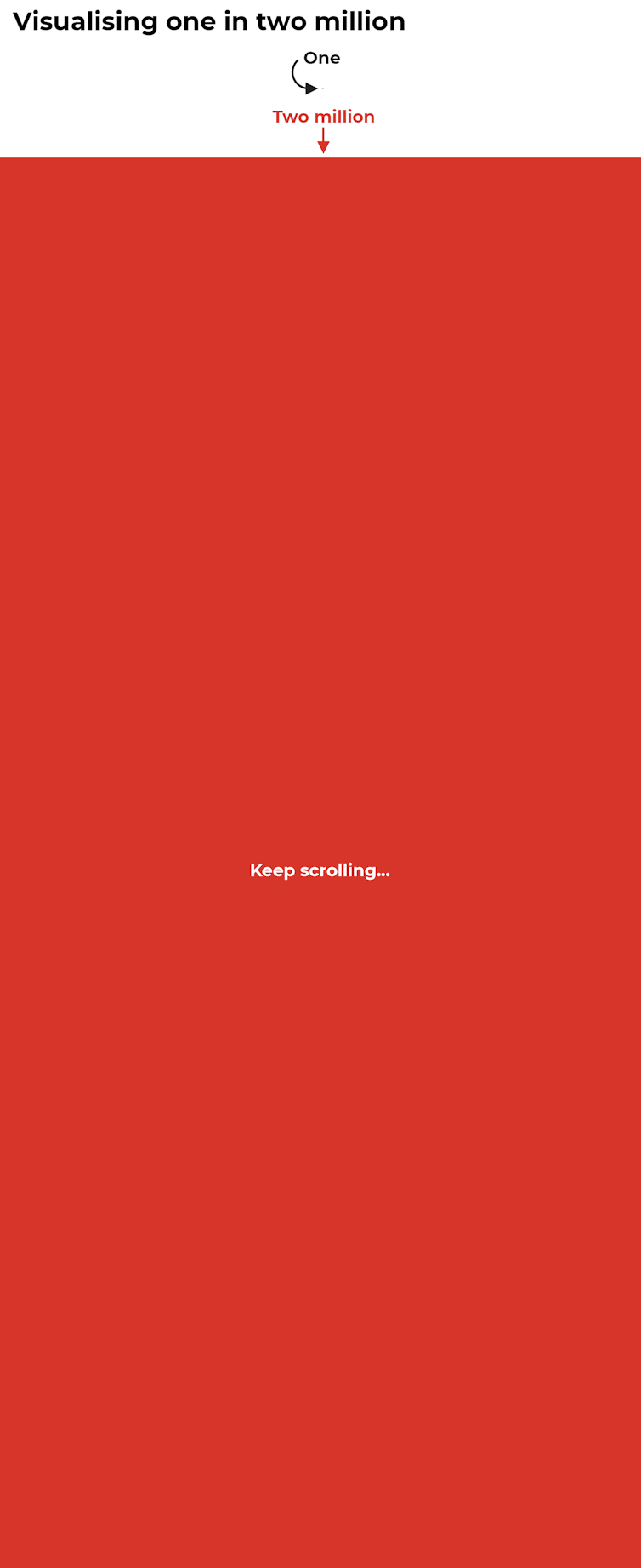

So let’s start with what we know about the risk of dying from TTS associated with the AstraZeneca vaccine, expressed the traditional way, with words and numbers. Then we’ll present the same numbers graphically.

Read more: Australians under 60 will no longer receive the AstraZeneca vaccine. So what's changed?

What’s the risk of dying from TTS?

Initially, we thought about 25% of people with TTS associated with the vaccine would die. But as we learnt more about how to recognise and treat these rare blood clots, the risk of dying from it has changed. In Australia, mortality is now down to around 4%.

This is a low risk of dying from a syndrome with a small likelihood of occurring. So we can express TTS risk in another way.

Two people in Australia have died from TTS after 3.8 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine delivered. This makes the likelihood of dying from this syndrome about 0.5 in a million, or if you prefer whole numbers, about 1 in 2 million.

Read more: A balancing act between benefits and risks: making sense of the latest vaccine news

And now, with graphics

Here’s one way of representing 1 in 2 million visually. This figure shows just how small this risk is. Are you ready for some scrolling?

As you can see, the risk of TTS is so small it is almost too small to communicate effectively in this format.

Perhaps even more visually powerful is to compare the risk of dying from TTS to other risks we face in our lives, using a risk scale. This allows you to compare a range of risks and put them into perspective.

As the risk of TTS is a one-off risk normally associated with the first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine, one interesting comparison is with other one-off risks, such as adventure sports.

As you can see, the risk of dying from TTS is far lower than many activities some of us get up to at the weekend.

But not all of us spend our weekends scuba diving or rock climbing. So let’s look at the more common risks we take in our everyday lives but do not pay much attention to.

This is not a perfect comparison, as the risks are averaged across the whole population, across the entire year. But it’s useful nevertheless.

So the risk of dying from TTS after the first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine is similar to the risk of being killed by lightning in a year in Australia. And this pales in comparison when compared to other risks, such as the risk of dying in a car accident.

So what happens next?

One of the challenges for public health has always been putting the risks and benefits of our health choices into perspective. This task is even harder when the risks involved are so small.

Using visualisations like these is one way to effectively communicate just how small the risk of TTS is and also put this risk into perspective by comparing it to other risks we incur in our lives.

When you fully appreciate how small the risk of TTS is, the decision to have the AstraZeneca vaccine to protect yourself and others becomes a much easier one to make.![]()

Hassan Vally, Associate Professor, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment